By Bryce

Christensen

“The dance,” declared the French

poet Charles Baudelaire, “can reveal everything mysterious that is hidden in

music . . . . Dancing is poetry with arms and legs.” Baudelaire would have found confirmation for

his words had he joined the hundreds who gathered in Cedar City’s Heritage

Center on April 21st for the Orchestra of Southern Utah’s concert

dedicated to the theme “Rhythm of Dance.”

Indeed, during the evening’s final and culminating number, Strauss’ Redetzky March, the audience thrilled not

only to the propulsive energy of a 19th-century waltz masquerading

as a march but also to the grace and precision of Southern Utah University’s ballroom

dance team, who waltzed across the stage and through the concert-hall aisles,

their every move a kind of “poetry with arms and legs” revealing “everything

mysterious . . . hidden in music.”

But long before SUU’s dancers made

their poetic and revelatory entrance, OSU’s gifted musicians had already imaginatively

conveyed their listeners to a half dozen ballrooms and dance halls. For as OSU President Harold Shirley made

clear in his welcoming remarks, this was an evening devoted to the magic of

dance.

And it was into the spritely

joyousness of French gavottes that OSU musicians first carried listeners,

beginning the evening with three movements from Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major. Under the baton of conductor

Carylee Zwang, the orchestra moved nimbly from one dance style to another, transitioning

from folk-dance gavottes in the first of the three movements selected for the

evening into the double-time rambunctiousness of a French bourrée in the second

and then finally into an exuberant French gigue, originally inspired by a

British jig, in the third and last.

Still in dance mode but playing at

the more courtly tempo of a minuet, the orchestra next performed the third

movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G

Minor. Under the direction of guest

conductor Qi Li, the orchestra seemed to metamorphose into an elegantly

bewigged18th-century ensemble providing regal music for dignified

aristocrats executing polished and deliberate dance moves--exquisite and

decorous--surrounded by palatial splendor.

But royal stateliness gave way to dance

rhythms bursting with romantic spontaneity when the orchestra next turned to two

of Dvorák’s Slavonic Dances, performed

under the baton of conductor Adam Lambert.

Beginning in a lilting and bucolic pastoralism, the first of these

numbers quickened into the wild passion of peasant couples hardly touching the

ground as they gamboled in wild delight.

This same electric intensity characterized the second of these Eastern

European folk dance, erupting in its first measures into a kind of tarantella-like frenzy before

modulating into a pacific interlude (giving doubtlessly exhausted dancers a

chance to catch their breath) before exploding again into sheer kineticism.

But the frolics of Eastern European

dancers faded away when the Orchestra performed as its fourth number Summer Dances by Brian Balmages, again

under the direction of Carylee Zwang. In

eerily unearthly tones, the opening strains of this dance-themed composition suggested

the alien choreography of some extraterrestrial dancers, perhaps those gracing ballrooms

on Neptune or Uranus. Mars must have

been the setting for the dances of a later passage marked by martial cadences

and military fanfare. But when the dance harmonies grew melancholy and dark,

listeners knew they had returned to the only planet where deep grief inspires

sorrowful mourning dances—like those found in Korea, Paraguay, and

Melanesia. Balmages’ harmonies redolent

with the pathos of deep loss ultimately yielded to concluding harmonies of

hope, reminding listeners that men and women who dance in mourning today may

dance in joy tomorrow.

It was decidedly American forms of

dance that first captured the limelight after intermission as the delighted

audience found itself hearing a premiere performance of Keith Bradshaw’s

specially commissioned composition American

Suite, a capacious celebration of the regional and ethnic diversity of

American dance, directed by Xun Sun. Who could resist the sashaying Southern

feistiness of the opening Charleston movement

or the rich and faintly melancholic nostalgia suffusing the Blue Ridge Waltz that followed? Likewise deeply engaging, the third movement,

puckishly named Flibberty Jitterbug,

captured all the spontaneity and creative freedom, all the restless sense of

emancipation, ignited by the jazz revolution of the Twenties, while the fourth

movement—Slow Me Down Blues—exposed

listeners to soul-piercing tones welling up from the same wells of feeling that

find voice in African-American work songs and spirituals. But it was the string-up-the fiddle-and-clap-your-hands

boisterousness of a Midwestern hoedown that swept over the audience during the

fifth and final movement, aptly named Dance

Down the Barn.

The standing ovation at the close of

this number recognized the exceptional gift Keith Bradshaw had given OSU

patrons with this splendidly variegated number, the remarkable musical vision

Xun Sun had demonstrated in bringing this composition to performance, and the

skilled musicians who had responded so ably to his baton.

But those rising for that ovation

were especially applauding the two featured soloists for this number: Keith

Bradshaw’s daughters Natalie Bradshaw on the violin and Hannah Bradshaw on the

viola. Both astonishingly poised for

their age, these two musical artists delivered every passage with complete

mastery and nuanced interpretation.

Laudable in their rendition of all five movements, these two rising

luminaries shone particularly brightly in Blue

Ridge Waltz, where Natalie’s ethereal violin poignantly complemented

Hannah’s deeply probing viola. Together,

the Bradshaws—father and daughters—left the audience indebted to them for their

collective musical contribution to the community. The Barlow Endowment for Music Composition

was instrumental in supporting the creation of this new music.

No sooner had the echoes of a

Nebraska hoedown died out than the orchestra transported the audience across

the Pacific to share in a very different kind of dancing. Quite appropriately, it was Qi Li who led the

orchestra in performing Dance of Yao, a composition

alive with the pulses of Chinese folk dance.

Unmistakably grounded in the natural rhythms of Chinese rural life and

of China’s yin-and-yang Taoist philosophy, this enchanting number brimmed with

the life of a verdant Chinese countryside.

Yet attentive listeners also caught the hints of China’s imperial

splendor as Asia’s Middle Kingdom. As a

memorable foray into one of the world’s oldest cultures, this number featured

four talented soloists. Violinist Ling

Yu (serving for this concert as Concertmaster) dazzled with passages by turns

tender and striving. Clarinetist Sarah Solberg poured a rivulet of liquid

euphony through her single-reed instrument.

Oboist Brad Gregory made his double-reed sing with a sonority beloved by

Mandarin and English speakers alike. And bassoonist Julie Kluber sent her baritone

double-reed plunging into the low registers where the earthiness of China

connects with the earthiness of America.

A

range of soloists also garnered appreciate attention in a number in which the

dance theme turned satiric—even burlesque—namely, Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld Overture, conducted by Carylee

Zwang. But the five soloists featured in

this number all captured the spotlight in the earlier passages of the number--before

the irreverent comedy broke out in the “infernal galop” (popularly known as the

“can-can”) late in the composition. Once again, Ling Yu demonstrated her rare

musicianship in drawing a lustrous brilliance from her violin, while Brad

Gregory again made his oboe an insistent instrument of enchantment. Adrienne Read breathed a stream of silvery

radiance through her flute, while Kendra Leavitt sent a cascade of glittering

notes out from her harp over enraptured ears.

And Leah Brown made the lyrical eloquence of her cello so potent that

listeners might have supposed they were hearing echoes of Orpheus’ own

lyre.

When, after the final Strass number,

strikingly complemented by the performance of SUU’s ballroom dance troupe, the

audience rose for a second standing ovation, they did so with a new awareness

of the relationship between ears that hear great music and of feet that waltz,

tap, salsa, tango, and otherwise dance in poetic and revelatory response to

that music.

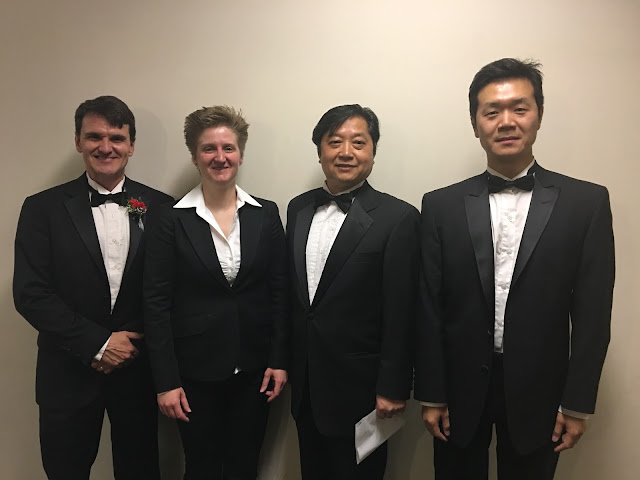

And though they did not whirl and

dance the way SUU’s ballroom couples did, the four conductors who took turns on

the podium performed their own valuable choreography, one that inspired

confidence that the exceptional leadership that Xun Sun has demonstrated as

OSU’s Music Director and Conductor for thirteen years is now influencing not

only the instrumentalists in the orchestra seats but also the assistant and

guest conductors who share the podium.

And, of course, the overall

choreography of the entire evening was possible only because of generous

sponsors—namely, Charles and Gloria Maxfield Parrish Foundation and Sally

Langdon Barefoot Foundation. These two

foundations helped defray the costs making this exultant festival of dance

possible.